Cold Case Closer

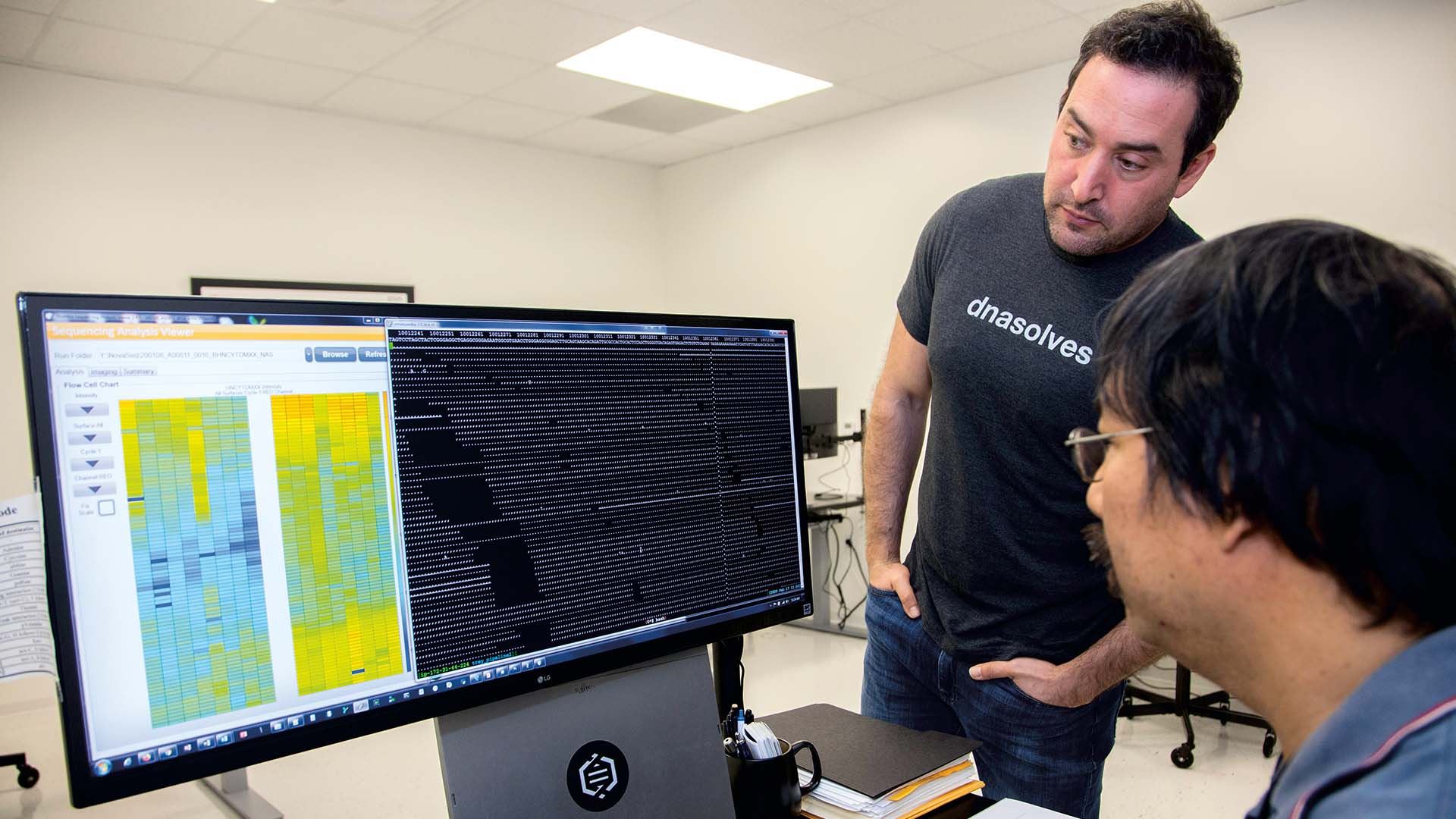

Dr. David Mittelman

After two decades of using his genomics expertise to seek solutions to medical mysteries, Dr. David Mittelman BS’01 shifted gears to solve a different kind of puzzle.

The University of Texas at Dallas alumnus founded a company to put cutting-edge genomics to work in forensics by teaming up with partners both public and private to answer unresolved questions of identity, particularly in the arena of law enforcement.

“I’ve been involved in DNA testing and genetics my whole working life,” Mittelman said. “For the last 20 years, I’ve focused primarily on medical research. Only recently did I become aware of the challenges in forensic science, and a group of us decided to see if we could make a difference helping solve cold cases.”

Beginning as a high school summer intern at UT Southwestern Medical Center and continuing as a neuroscience undergraduate at UT Dallas, Mittelman had a unique opportunity to play a part in one of the most consequential biological explorations in history. He contributed to a UT Southwestern effort by building instrumentation and robotics to help automate and streamline the sequencing of the first human genome.

Meanwhile, in his undergraduate coursework at UT Dallas, he found inspiration in a class taught by Dr. Michael Kilgard, the Margaret Fonde Jonsson Professor of neuroscience in the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences, and interim executive director and chief science officer of the Texas Biomedical Device Center.

“Dr. Kilgard noted that there are 100 billion neuron connections but only tens of thousands of genes, so early on I figured — perhaps naively — that it would be easier to approach questions from a genetic standpoint,” Mittelman said. “That nudged me further along this path. I loved what I was doing at UT Southwestern, and so I pursued graduate work in genetics and biochemistry.”

Mittelman earned a doctorate in molecular biophysics from Baylor College of Medicine. After a stint on the Virginia Tech faculty and a few years at companies devoted to medical and personal genomics, Mittelman shifted his focus. He founded Othram in 2018 in The Woodlands, Texas, just north of Houston.

Othram is the world’s only laboratory purpose-built to combine genome sequencing with advanced human identification applications. The laboratory is also the only facility in the U.S. or Canada offering end-to-end, in-house processing from forensic evidence to investigative leads. Over the last three years, this technology has helped law enforcement crack cases at the local, state and federal level, many of which had been unsolved for decades.

“Cold cases highlight an important humanitarian opportunity for our lab,” he said. “Othram can digitize and immortalize evidence from crime scenes or human remains — evidence which otherwise can age and degrade or be lost.”

His goal, he said, is to make sure fewer people “slip away.”

“We can gather information from forensic evidence and empower law enforcement to tell the rest of that story,” he said. “It’s an amazing and rewarding feeling to be able to help re-anchor people who have been lost to society because they are unidentified.”

Othram’s trademarked approach, called Forensic-Grade Genome Sequencing, uses proprietary laboratory methods, computational algorithms and database resources to reconstruct DNA markers from small fragments of DNA extracted from limited or degraded forensic evidence.

“We use this information to learn as much as we can about an unidentified person so we can help law enforcement determine their identity,” Mittelman said.

In one recent project, Mittelman’s team helped to identify a woman who died in 1881 based on DNA extracted from her bones.

“It is one of the oldest cases solved this way, and it highlights what can be done with this technology,” he said.

“We … learn as much as we can about an unidentified person so we can help law enforcement determine their identity.”

In August 2021 Othram assisted in identifying the man responsible for the death of Fort Worth teen Carla Walker, who was raped and murdered in 1974. Glen McCurley pleaded guilty and was sentenced to life in prison. An episode of NBC’s “Dateline” describing the case aired in January. And last September, the company helped identify Clara Birdlong, one of the remaining unidentified victims of serial killer Samuel Little, who has confessed to 93 murders committed between 1970 and 2005.

Mittelman expects such resolutions to become more common and hopes that increasing rates for solving cold cases can become a deterrent to crime.

“People will come to realize that they will eventually get caught, and that hopefully will serve to reduce serial crimes, especially sexual assaults,” Mittelman said.

In February, Mittelman received a 2022 Distinguished Alumni Award from UT Dallas. His advice for individuals considering any career path is to find where your talents and passions meet the demands of the world.

“When I started out, I wanted to learn everything there was to learn about the human genome. I certainly didn’t expect to be helping law enforcement solve decades-old cases,” he said. “I think it is a good idea to stay open-minded, be open to new opportunity, and be flexible in how and where you apply your effort. I try to self-reflect as much as possible on what I am doing and how it might make the world a better place.”

– Stephen Fontenot