Bees & Butterflies

by Robin Russell

“Go to the bee, thou poet: consider her ways and be wise.”

— George Bernard Shaw, Man and Superman, 1903

Most people would be somewhat wary around a beehive buzzing with thousands of stinging insects. Scott Rippel MS’96, PhD’99 practically goes into Zen mode.

For Rippel, a senior lecturer in biological sciences at The University of Texas at Dallas, working with honey bees is more than a way to educate the campus community about the importance of pollinators — it’s an experience.

“When I open up a hive and I have 10,000 to 50,000 bees around me buzzing, my focus goes right to them. Everything else melts away. All my stresses disappear,” Rippel said.

As relaxing as Rippel finds it, keeping bees is not just a hobby. The beehives he established on the UT Dallas campus give students firsthand experience with pollinators that are essential to the food supply.

Consider that nearly one-third of the food humans consume — including most fruits and many vegetables — is dependent upon pollination. When pollinators, such as bees and monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus), transfer pollen from one flower to another, they fertilize the plant so it can grow and produce fruits and seeds, which are important components of a healthy diet.

But key pollinator species have suffered a drastic decline due to invasive pests, increased pesticide use, habitat loss and changes in climate.

Bees in general have suffered a 40 percent population drop each year since 2011, and the monarch butterfly has declined 90 percent in the last two decades. What’s more critical is that these indicator species may be predictors of how the environment is affecting other species as well, said Rippel.

The ongoing risks for pollinators has prompted the UT Dallas campus community to highlight their role and help protect their delicate ecosystem.

The University is intentional about growing native prairie grasses and plants, using least-toxic pesticides and maintaining pollinator-friendly habitats in the campus landscaping, which includes 15 beehives and four monarch waystations.

The nation’s multibillion dollar agricultural industries are highly invested in seeing that the bees do well, and, in particular, supporting the vital contribution of the European honey bee (Apis mellifera). Beekeepers breed and manage these honey bees carefully, ship them around the country to pollinate dozens of crops — including almonds, apples, cherries and plums — and work overtime to replace any losses.

As a result, the U.S. population of European honey bees hit a 22-year high in 2016 before dipping slightly in 2017, according to figures from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

But other species of bees have not fared as well, including native species that offer beneficial competition to help honey bees pollinate more efficiently. In 2017 the rusty patched bumble bee (Bombus affinis), a prized pollinator once familiar to much of North America, was the first wild bee in the continental United States to be listed as an endangered species.

Senior lecturers Dr. Christina Thompson and Dr. Scott Rippel give the mini-Whoosh sign during a successful beehive installation at one of the apiaries on campus.

Senior lecturers Dr. Christina Thompson and Dr. Scott Rippel give the mini-Whoosh sign during a successful beehive installation at one of the apiaries on campus.The Bee Man on Campus

At UT Dallas, Rippel easily has a reputation for being the bee man on campus. The decorated U.S. Army veteran earned both his master’s and doctoral degrees in molecular and cell biology from the Department of Biological Sciences in the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics and has been teaching at UT Dallas since 1999.

When he launched his Honey Bee Biology class in 2012, word of his expertise spread across campus. The perennially popular survey course teaches biology undergraduates the insect’s biology, behavior, social organization and role in the environment and agriculture.

To give his students and other interested volunteers firsthand experience with bees, Rippel helped establish 15 beehives on two apiaries at UT Dallas.

He estimates he’s been stung more than 75 times, but it doesn’t seem to faze him. Students hardly see him flinch.

“Now I get stung, and it’s like a mosquito bite,” Rippel said.

It wasn’t always that way. Rippel recalls being fascinated as a child, but wary, around the beehives on his grandfather’s acreage in Pennsylvania.

Whenever his grandfather donned his beekeeper’s suit, Rippel knew to stay out of the apple orchards where the hives were located.

That caution came into play again a few years ago when Rippel discovered a swarm of bees in his own yard. To protect his then-3-year-old daughter, he reached for an aerosol can of bee killer, only to realize he was out of the pesticide. By the time he got to a hardware store, it was too late.

“The next day, the bees were gone. I was just fascinated by that,” Rippel said.

He decided to study the life cycle and workings of honey bees, reading books such as Thomas D. Seeley’s Honeybee Democracy. His interests were piqued further when a student at UT Dallas showed him a feral beehive he had found on campus.

“I was just enthralled with it. I couldn’t believe I was just feet from it. By the time I got home that night, I had decided to keep bees,” Rippel said.

Honey Do’s and Don’ts

The humble honey bee has long fascinated nature lovers. Among the 20,000 mostly solitary species of bees, the fuzzy-looking honey bee is unique in that it lives in an incredibly complex society.

Peek under the lid of a beehive, and you’ll see thousands of bees working together for the good of the colony. They look for ways to help out: building, cleaning and guarding the hive, gathering food, feeding the population, and keeping larvae and young bees warm — all without supervision.

But more than efficient workers, bees and other pollinators, like monarch butterflies, perform a vital task. Honey bees contribute more than $14 billion annually to the U.S. agricultural industry by pollinating more than 100 commercial crops, according to the USDA. They’ve even been given agricultural status. Simply put, bees keep plants and crops alive.

But pollinators in general have declined in number due to disease, habitat loss, pesticides and climate change.

Bees in particular are plagued by a parasitic insect called the Varroa destructor mite. When the tick-like insect infects a beehive, the entire colony will die within two to three years. The solution is tricky.

“We’re looking at killing a bug on a bug, and that’s difficult. In the end, we’re having to use chemicals,” Rippel said.

Bees are also suffering because urban encroachment and mono-cropping that is profitable for farmers have diminished the habitats that provide bees with the nutrition they need. Without diverse flora, native pollinators lack breeding grounds and food sources to support their crucial role in maintaining flowering and food-producing plants.

“Bees have a short window of time to collect their carbohydrate source, which is nectar, and their protein source, which is pollen. They store enough pollen to produce enough bees, and they hoard nectar in the form of honey to warm their colonies in the wintertime,” Rippel said.

At UT Dallas, students maintain the campus hives and harvest honey at the micro-apiary that was added on at the south end of campus, thanks to a gift to the Hobson Wildenthal Honors College from Nature Nate’s, a honey company in McKinney, Texas.

Biology senior Kelsey Lyle grew up in a family of nature lovers and was always intrigued by bees. Although she had no way to keep bees herself while living on campus, she decided to learn more about them by joining the Collin County Hobby Beekeepers Association and the Texas Beekeepers Association.

One day she asked Rippel if she could help with the hives on campus, which students have christened with such whimsical names as the “Zommbee” and the “Air-Bee-n-Bee.” Lyle now manages one of the hives and has become expert at marking the queens to track generations. She also teaches basic beekeeping to other students.

“The whole system within the hive is so intricate and nuanced. There are things you can discover that are just fascinating,” Lyle said. “If there is more than one queen laid, the first one stings and kills the others. It’s a real-life ‘Game of Thrones.’”

As an intern with the University’s Eco-Rep program — student leaders who implement sustainability programs on campus — Lyle has tracked the metrics that helped UT Dallas gain the Bee Campus USA designation. The University accomplished that by raising awareness and developing a pollinator-friendly habitat and a least-toxic pest-management plan.

“We’ve formalized what we had already been doing,” said Lyle, who hopes to eventually work in ecology or environmental science.

“I think we depend on pollinators a lot. I can get tunnel vision, being in college. But it’s important to know what’s going on around us, to know that what I’m doing affects what will happen later on,” she said. “This is not just learning for learning’s sake. This will impact life.”

“We want people to be aware of what bees are, why we need them and how they affect our lives.”

— Dr. Christina Thompson

Besides tending bees and planting milkweed to attract monarch butterflies, students participate in sustainability experiences through Alternative Spring Break service projects, by working a plot in the on-campus Community Garden or signing up for tree-planting events.

Mackenzie Hunter, director of the Office of Student Volunteerism, helps oversee some of those projects. She also taught a course about food security and sustainability last spring. The class explored how localizing food production can help people who lack reliable access to nutritious food. As part of the course, students installed a beehive, harvested honey and collected produce from the Community Garden, which is managed by the Office of Student Volunteerism, to donate to food pantries.

“Food is such an important part of who we are and how we connect to other people. I think it’s our responsibility to reconnect with food and where it comes from. Pollination is a big part of that,” Hunter said.

Students have become increasingly interested in bees, said senior lecturer Dr. Christina Thompson, who oversees an honors college reading class on honey bees and society. The class studies the behavior of bees, including swarming and hive reproduction, as well as the potential threats to the insect’s survival. Though the class is targeted to freshman students, seniors often fill up the class first each semester.

“They all want to go see the bees. They’re curious about them. There is a bit of anxiety — it’s kind of an adrenaline rush. But bees aren’t aggressive; however, they are defensive about their homes,” Thompson said.

Thompson and Rippel also take their passion for bees to students outside of their classrooms and into the broader community. They give talks on sustainability to Eugene McDermott Scholars and Community Garden volunteers; they bring a frame of live bees to show students during Earth Week; and twice a year they take an observation hive to the Rory Meyers Children’s Adventure Garden at the Dallas Arboretum and Botanical Garden.

“We want people to be aware of what bees are, why we need them and how they affect our lives. There’s a delicate system out there that we don’t fully understand, and as long as we don’t understand it, we should leave it as intact as possible,” Thompson said. “We need to understand how we effect change by the choices we make.”

They also share the modest honey crop produced by the campus bees, which is usually enough for students in their classes to experience. The diverse flora on campus lets bees gather nectar from plants like Indian blanket, Queen Anne’s lace, canola, horsemint, aster and goldenrod. Each plant contributes to the flavor of honey.

The campus bees also benefit surrounding neighborhoods by pollinating suburban homeowners’ gardens.

“The University can gain by showcasing these things,” Rippel said. “What we do here doesn’t impact on the agricultural issue; what we’re trying to do is education and outreach about what we’re doing to our environment.”

The Butterfly Whisperer

If Rippel is the bee man on campus, Craig Lewis, the greenhouse and landscape coordinator for the Office of Facilities Management, is the butterfly whisperer.

Lewis has admired the iconic black-and-orange monarch butterflies since he first witnessed their annual migration. One day, he saw a band of them about 500 yards wide and nearly 1 mile long approaching campus on their route to Mexico.

“We were absolutely on the path. We had a lot of open field around campus at the time, and it was not closely maintained. We were rife with milkweed, and there were countless numbers of migrating butterflies. It was just joyful to see,” Lewis said.

He took a special interest in monarchs after noting their decline over the years. Once the most well-known insect on the planet, the monarch butterfly is becoming scarce because of habitat loss and the use of pesticides that are not target-specific. Since 1990 about 970 million have vanished, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The insect is currently under review for endangered species status.

Whatever befalls the monarch might affect other insects as well, Lewis said.

“Monarchs are the canary in the coal mine for the entomology world. They’re the tipping point for a whole list of insects that are on the verge of extinction,” Lewis said.

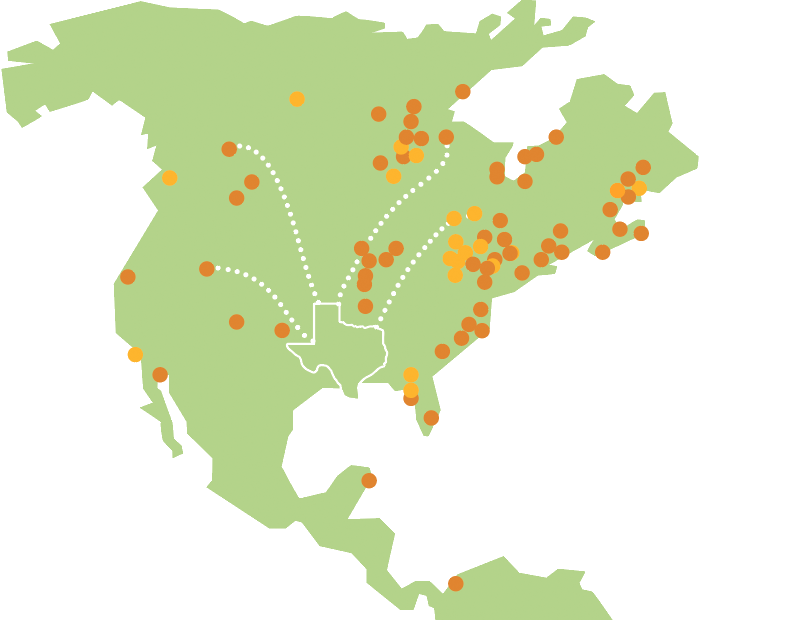

Concern for monarchs prompted a nationwide movement to plant milkweed, the only plant on which monarchs lay their eggs and nourish their young caterpillars. Once a plentiful native plant, milkweed is in steep decline because it is of little use to farmers. Experts believe monarchs could become extinct if the supply of milkweed is not restored. Monarchs are unique in that they are the only insects that every autumn travel more than 3,000 miles from Canada to Mexico, where they spend the winter. Generations of these butterflies somehow return to the same few acres in Mexico. Entomologists are still studying how they know when to leave and where to travel. Their northbound return trip in April is when the campus monarch waystations are most populated.

Knowing that UT Dallas lies directly on the monarch migratory path, Lewis approached Thea Junt MS, MBA‘16, former associate director for energy conservation and sustainability, in 2014 about creating a plan to plant milkweed on campus to attract monarchs and ultimately help rebuild the butterfly population.

“I said, ‘We’re sitting in the middle of the Blackland Prairie. Why don’t we rehabilitate it and see what happens?’” Lewis recalled. “When we quit mowing, the milkweed came back, along with native buffalograss.”

Lewis has since planted the six different varieties of milkweed native to the area, some for nectar that appeals to butterflies, some for them to lay eggs on. He collected and purchased seeds and then grew them in the campus greenhouse after refrigerating them for a month to help them germinate.

“Monarchs are the canary in the coal mine for the entomology world.”

— Craig Lewis

Students also help by planting the milkweed on campus during Butterfly Flutterby events, sponsored by the Office of Student Volunteerism. Thanks to the University’s efforts to nurture these species-specific plants, UT Dallas has been named an official waystation for migrating monarchs by Monarch Watch, a conservation program focused on the butterfly.

Four certified monarch waystations on campus serve as landing places for the butterflies during their annual migration: the disc golf course, the east side of the Eugene McDermott Library, outside a parking structure on the northwest side of campus and near the Community Garden.

The University made operational changes, too. Staff planted more native perennials near the waystations and in patches across campus to further attract butterflies instead of planting annual color plants. The native pollen and nectar-bearing wildflowers planted include Black-eyed Susan, American basket-flower, Gayfeather, Maximilian Sunflower, Mexican Hat, Greenthread and Texas Bluebonnet.

These pollinator-friendly patches are seen in “no-mow” zones across campus, alongside parking structures, outside office buildings and just yards from the campus Community Garden, which includes an herb garden with a host plant for swallowtail butterflies.

Planting milkweed and wildflowers is a win-win for pollinators and the campus, Junt said.

“It’s all about the choices we make. It’s a buffet for pollinators. You have to keep flowers going all year-round. That’s the ‘come hither,’” Junt said. “Native plants and wildflowers also save water, and they’re beautiful. It’s smart Texas landscaping.”

Keeping monarch butterflies happy improves the landscape for all pollinators, added Gary Cocke, the current associate director for energy conservation and sustainability.

“It’s the right thing to do. Our indicator species are suffering, and we are right on their migratory path. They have adapted to certain plants, so adding this biodiversity is critical,” Cocke said.

Best of all, students who participate in sustainability projects will take their knowledge with them as they graduate.

“Our students are going to become homeowners themselves one day. They know that the way we landscape matters. A landscape that’s just grass doesn’t do it for pollinators,” Cocke said.

Simplified migration view map of reported monarch sightings through October 17, 2018.

Cultivating Sustainability Leaders

One of the ways UT Dallas students help raise awareness about the role of pollinators is by serving as interns for the Eco-Rep program in the Office of Sustainability.

Eco-Reps advance sustainability issues through education, outreach and project leadership. Their goal is to help students become eco-friendlier and learn about sustainability issues. Each Eco-Rep takes charge of a specific project, such as reporting and collecting data for the Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System of the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education.

Other leadership projects include completing a greenhouse gas inventory, developing and implementing materials for green practices in teaching labs, recognizing graduates who have volunteered with sustainability projects, developing the Bee Campus USA application and co-chairing the Bee Campus USA committee to support a pollinator-friendly habitat.

Eco-Reps also plan Earth Week activities, collect data for Recyclemania, build beehives for campus use, plant milkweed plants for monarch waystations, build worm composting bins for use in apartments and residence hall rooms, and make shadow boxes to illustrate what items can be recycled.

Delaney Conroy, a senior in the School of Arts, Technology, and Emerging Communication, became an Eco-Rep after volunteering in the Community Garden on campus and at the Texas Worm Ranch in Garland.

“I was hooked and couldn’t get enough,” Conroy said. “I learned that I grew up far more green than most. Being able to share my knowledge is one of my favorite aspects of being an Eco-Rep.”

Conroy recently helped build and maintain the new Blanco Botello Garden, dedicated in 2016 to honor a former Office of Facilities Management staff worker. Conroy planted vegetables and herbs, and sets out the harvested produce for facilities staff to enjoy.

A rain catchment at the garden was established through the Student Government Green Initiative. The barrel allows the garden to be watered from harvested rainwater.

“A little work goes a long way, and it’s worth it to make our campus a little bit eco-greener,” Conroy said.

Attracting Monarch Butterflies

Home gardeners who wish to cultivate a monarch-friendly environment can plant many varieties of milkweed and other plants.

Engelmann’s Milkweed (A. engelmanniana)

Side-Cluster Milkweed (A. oenotheroides)

White-Flower Milkweed (A. variegata)

Green Milkweed (A. viridis)

Antelope-Horns (A. asperula)

Swamp Milkweed (A. incarnata)

Slim-Leaf Milkweed (A. stenophylla)

Sandvine (Cynanchum laeve)

Tropical Milkweed (A. curassavica)

Slim Milkweed (A. linearis)

Butterfly-Weed (A. tuberosa)

Wand Milkweed (A. viridiflora)

Green Milkweedvine (Matelea reticulata)