A Seven Year Transformation Project is Complete

By Gaile Robinson

Editors’ Note: This feature appears as it was published in the fall 2016 edition of UT Dallas Magazine. Titles or faculty members listed may have changed since that time.

In the hours before indie music duo Alex & Sierra performed in a new nook of campus known for its bubbling illuminated fountains and grassy lounge areas, physics senior Shawhin Talebi saw to the technical details during an afternoon sound check.

He expected a good turnout for the winners of the X Factor, Season 3 television competition, but he was a bit surprised when people started arriving well before the concert’s 7 p.m. start. In fact, the crowd that March evening swelled to 1,200 students, who sang and swayed on the newly renovated plaza between Founders Building and the Erik Jonsson Academic Center.

It was a scene many years in the making.

Alex & Sierra perform for students. In between songs, the duo chatted with the crowd.

Alex & Sierra perform for students. In between songs, the duo chatted with the crowd.

For Grace Bielawski Richards BA’11, that part of campus used to house a cordoned-off, nonfunctional water feature that had become an eyesore. When she arrived on campus as a freshman McDermott Scholar, the atmosphere was a concrete “ghost town,” she recalls. But during her time at UT Dallas, she saw the first phase of a campus transformation begin to dramatically change the landscape before her graduation five years ago.

The area between Founders Building and the University Theatre, now known as Texas Instruments Plaza, includes stone-edged grassy tiers around a bubbling ground-level fountain. Pictured below is the earlier concrete-laden version of the area, including a nonworking fountain.

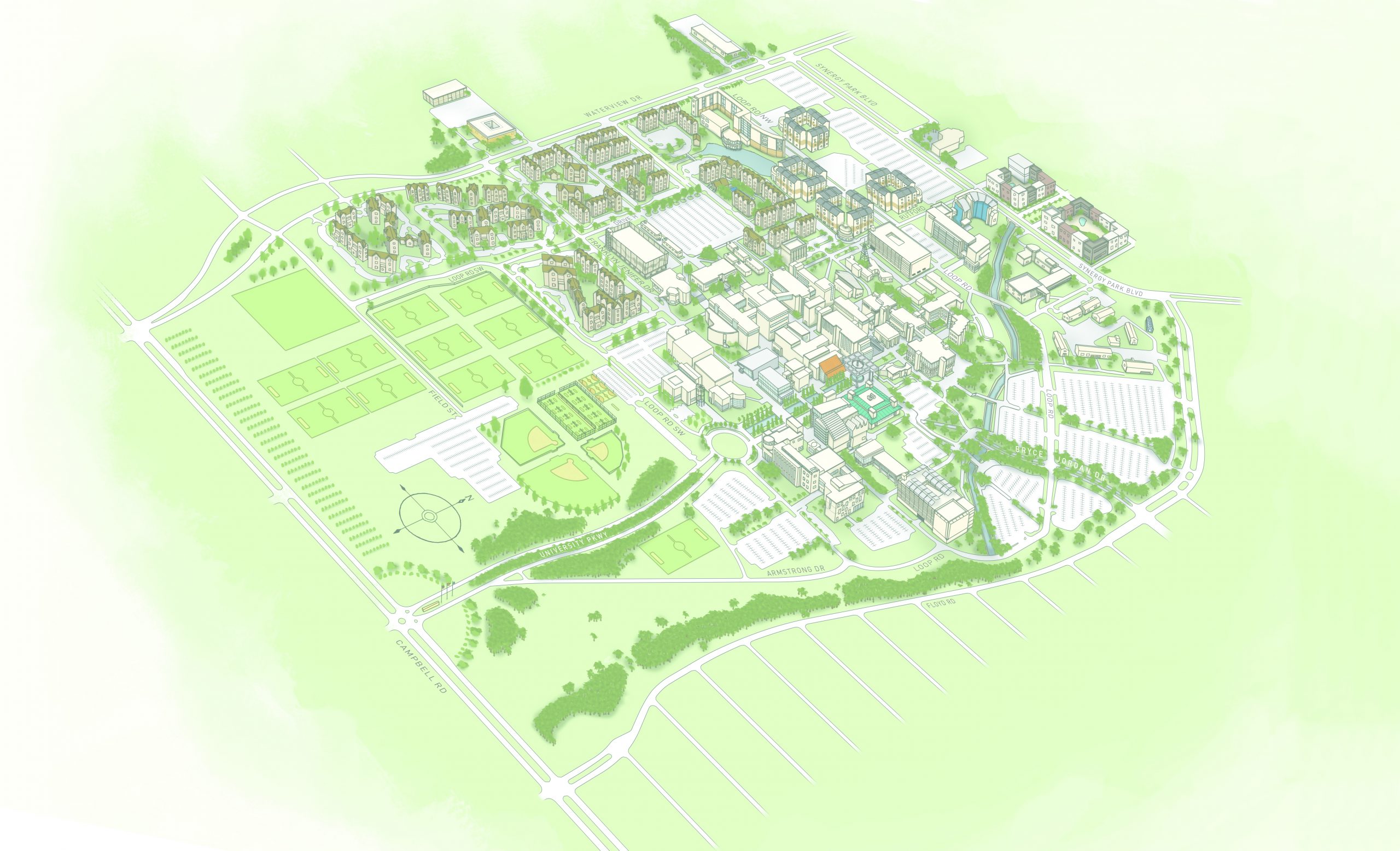

Richards has watched from afar as the two-phase Campus Enhancement Project reached completion, representing a $45 million investment since 2008 by longtime supporter Margaret McDermott and other private donors. And just as the transformation project renewed the grounds and the outdoor campus experience, a cadre of new buildings has forever altered the field of sight for anyone walking through UT Dallas.

“Campus seems more inviting with the integration of the buildings and the landscaping,” Richards says by phone from Washington, D.C., where she works as a lawyer in the Offices of the U.S. Attorneys. “The tone is set as you walk through campus. It makes you want to linger outside a little bit.”

This fall, the class of 2020 are the first freshmen to attend the University now that the landscape project is considered complete.

The seven-year overhaul brought an iconic trellis with misters and climbing wisteria, inviting walkways and visiting spots, and signature reflecting pools lined with magnolia trees. But more than its individual features, most agree that the project has given the campus a heart.

All About the Students

Physical appearance offers more to a campus than just a beautiful exterior; aesthetics also have a direct effect on the quality of an education, a subject researched by C. Carney Strange and James H. Banning, experts on campus environments.

In their 2015 book Designing for Learning: Creating Campus Environments for Student Success, the authors’ elements of successful design include dorms, classrooms and such, but they also acknowledge the virtues of more ephemeral zones.

“Much of college is about what happens outside the classroom,” says Richards, who was student government president during her senior year. “So to have a space to reflect that reality is important. A lot of what happens is socializing and learning who you are and what you might be doing with your life.”

As an undergraduate, Richards was among the student leaders who advised officials on features for landscaping and buildings.“I felt like UTD students were a part of making things happen there,” says Richards, who went on to law school at the University of Virginia. “By contrast, UVA is very tradition bound, still looking back to the days of Thomas Jefferson. At UTD, we are still establishing traditions and still building. It was exciting to be a part of something so new and responsive.”

Nondescript Origins

The United States is known for its world-class campuses, from the University of Virginia, which was designed by Jefferson, to the Yale University campus that is a national treasure, writes James Howard Kunstler, author of The Geography of Nowhere: The Rise and Decline of America’s Man-Made Landscape.

Universities established long before UT Dallas frequently have a tree-bordered lawn anchored at one end by an administration building. Popular into the early 20th century, the design is reflected in the Lawn at UVA, the malls (south, east and west) at UT Austin and the Quad at Stanford.

Kunstler says, “Virtually every school has a great old quadrangle or other good public place at its heart. But as they get away from the center of campus, things begin to dribble away.” “Dribble” accurately describes the state of UT Dallas before the campus transformation got underway. The early buildings lacked architectural snap and offered little hint of what the interiors might house. Ponderous relics of the ’60s and ’70s, the first structures mimicked the short-lived Brutalist style of architecture that was known for fortress-like exposed concrete construction. The campus had the air of a charmless industrial park.

This archival photo lends credence to the “concrete canyon” description of the mall prior to renovation.

This archival photo lends credence to the “concrete canyon” description of the mall prior to renovation.UT Dallas hardly stands alone in its nondescript origins. Many universities that grew exponentially after World War II suffer the same plight, with buildings that have no relationship to the landscape or to each other. Instead, they are islands surrounded by seas of asphalt.

Back in the early days, before UT Dallas was established in 1969, the campus was known as the Graduate Research Center of the Southwest. There was one building and one parking lot. “You could park right next to the front door,” remembers Dr. John Hoffman, who first worked at the research center and then as a physics professor at UT Dallas.

Those front-door parking spots no longer exist. Over the years, each new building has forced another parking lot farther into the surrounding acreage that Hoffman remembers as cotton fields.

Even after the research facility became a research university expressly for upperclassmen, it did not look like a traditional campus. Physically it was more corporate than collegiate. With few classes offered during the day, most students arrived after the sun went down.

In contrast to the University’s earlier years with few daytime classes, the growing student enrollment has brought increased activity to the mall throughout the day.

“The place was a wasteland until 6 at night,” says Mary Walters, who recently retired as director of the Student Union. “During the day, you could walk across campus and not see a single soul.”

Then, in 1991, freshman and sophomore classes were added, bringing students to the University both day and night. The campus was enlivened.

But the aesthetic problems multiplied. Insistence on close parking coupled with the University’s continuous construction resulted in a campus of concrete. Acres of parking lots surrounded clusters of buildings.

Something had to be done. So, the Campus Enhancement Project, which focused on landscape and design, was created. The effort drew upon one of the University’s strategic initiatives to enhance the physical appearance of the campus.

The aesthetic need was apparent. But how to fund the project was not as obvious, especially when the cost of such refinements was more than that of a new building.

Championing the project was someone intimately familiar with the University—Margaret McDermott, the wife of the late Eugene McDermott, co-founder of UT Dallas and Texas Instruments. She fully understood the need and generously contributed to the project.

Shortly after McDermott and donors stepped forward, Peter Walker of PWP Landscape Architecture was brought in to help shape the project. He is known in Texas for designing the grounds of the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas with Italian architect Renzo Piano and for projects at UT Austin.

Walker’s credits are global. He has worked with architects on commissions for the National September 11 Memorial & Museum in New York City, the U.S. Embassy in Beijing, Novartis headquarters in Basel, Switzerland, and the Library Walk at the University of California, San Diego.

When the enhancement project for UT Dallas was first broached, “we were asked to do a little plaza up by the student center to enrich the school,” Walker says in a phone interview from his office in Berkeley, California. He realized immediately that what was needed was more than a plaza. It called for an entire game plan.

The game plan went beyond landscaping, proposing placement of new buildings on a grid and suggesting design elements.

“There was no focus,” he says. “There was a jumble of buildings built when it was popular to use tan concrete and black glass. The buildings had been put up so fast that there wasn’t any landscape.

“UT Dallas is an increasingly important part of the UT System, yet it was practically nondescript,” Walker says. “Anyone visiting for the first time would have no memory of it.”

That’s hardly an ideal identity for a young university with national aspirations like UT Dallas.

The Game Plan

So, with a mandate from the University and its benefactors to fix the ugly and bring on the beauty, Walker suggested a two-part landscaping assault that came with a $45 million price tag.

“A formal expression first, with a continuous vocabulary formed by the trees, walls and benches” is what Walker proposed for the initial phase that would renovate the mall from the center of campus to the south end and the Campbell Road entrance. The first phase, completed in 2010, was built to welcome visitors with an impressive campus entry.

A more relaxed focus was taken in the second phase, converting the north end of the mall to a parklike environment. That project began in 2013 and wrapped up in 2016.

“It doesn’t have to be casual like a backyard, but there does have to be something that enables people to move around comfortably,” Walker says of the section that extends to the Administration Building on the north side of campus.

Authors Strange and Banning refer to such areas as “restorative places,” which are usually in a setting with a designed water feature, gardens and park areas. What the Campus Enhancement Project has produced is a bounty of each, stately and whimsical, wild and restrained, and — most importantly — memorable.

Fewer and fewer vestiges remain of the concrete canyon. “One of the real positives of the project’s site plan is a greater understanding of the value of the land. To create a pedestrian campus, we need to make it as compact as we can, rather than spread out,” says Rick Dempsey, associate vice president of facilities management. “We needed to densify the core of the campus.”

Engineering student Emiola Banwo, who has been a student since 2010, has noticed an enormous change in the number of students he sees on campus. He attributes the increased activity to the new landscaping efforts. “It’s beautiful; it’s paradise,” he says.

The plan addressed a number of concerns: thoughtful placement of buildings, more casual congregation areas, improved walking paths and environmentally friendly plantings. Additionally, choices in landscaping and permanent structures create aesthetically attractive boundaries with the surrounding neighborhoods.

Instead of hiding the campus from the neighborhood with a screen hedge, UT Dallas hides its parking lots. Edges of campus are framed with trees and plantings, offering enticing glimpses to passersby.

There are other, more subtle features. When Walker first toured the campus, he was told that the University doesn’t have a football team but was home to a national class chess team. So, whoosh, the inspiration for Chess Plaza was born. The area between the Student Services building and the Naveen Jindal School of Management is now bedecked with four human-size chessboards.

“Our goal,” says Dr. Calvin Jamison, vice president of administration, “has been to transform campus into a vibrant environment that reflects the quality of our academics and caliber of our community. This requires the right mix of buildings, residences, landscaping and infrastructure to create a next-generation urban university.”

Stone stacked benches along the mall provide students with places to reflect, stude and create.

Such attention to detail helps recruit students. Arden Wells BS’16 from New Orleans, toured the University of Virginia and Southern Methodist University, both of which have traditional brick, ivy-covered buildings in the classic style. “My initial perspective of UTD was that it did look like a college campus, but not like the old ones. It looked futuristic, which is cool.”

She’s speaking Tom Lund’s language. Lund, an architect with the UT System Office of Facilities and Planning, says, “We are developing a new campus architectural vocabulary that centers around transparency in the buildings. For instance, we are incorporating a lot of daylight and glass curtain walls.

“We started with an overall landscape design that has now given us the guidelines, the grid, the structure, to carry into the future,” Lund adds. “That was brilliant.”

Lund notes that building construction has placed similar priority on energizing student collaboration.

“For example, we are putting in wider corridors with lots of power outlets, so that there is room to gather,” he says. And, he adds, several of the buildings have amphitheater- like spaces, repeating indoors what has been so popular on the mall.

The physical change on campus, both indoors and out, has enhanced the experience — aesthetically and psychologically — for new students, former students, faculty and staff. It is part of the transformative package envisioned by many and brought to life by Peter Walker.

“A university experience changes everyone’s life,” he says. “That is what it is supposed to do.”

A Picture of Success

Nineteen buildings were constructed at UT Dallas in its first 40 years (1964-2004). Since 2005, 27 new buildings have been added. Vice President of Administration Calvin Jamison said, “We are creating a legacy of excellent facilities and infrastructure. With more buildings, services and a transit-oriented development adjacent to campus, UTD is becoming a destination of choice.”

The University’s physical metamorphosis coincides with its emergence among the nation’s research institutions. Learning and living spaces have doubled. Buildings and walkways are accented by the installation of thousands of trees, native plants and shrubs. Plazas, plinths, fountains and terraces punctuate the outdoor environments. New structures are sited to make the most of the campus improvements, with careful attention to building interiors that connect students with each other and the outdoors. Here are some of the new features.

New Additions

The 10. Callier Center for Communication Disorders on-campus facility expansion and 11. Parking Structure 4 opened in the fall. The Brain Performance Institute building in Dallas is scheduled to be finished in 2017.

Housing

This fall, co-developers Balfour Beatty Campus Solutions LLC and Wynne/Jackson Inc. opened 12. Northside, a mixed-use residential and retail development on Synergy. On the southwest side of campus near the soccer fields, Student Housing Phases VI and VII are underway. The two apartment-style complexes are expected to provide a total of 800 new beds on campus for fall 2017.

Visit the utdallas.edu/pardonourprogress website for additional updates on these and other projects on campus.