The Heart of an Island

By Aphrodite Vati Mariola BS’97

Editors’ Note: This feature appears as it was published in the fall 2016 edition of UT Dallas Magazine. Titles or faculty members listed may have changed since that time.

ON APRIL 27, 2015, my life and dreams changed forever. Members of my family and I were preparing the Aphrodite Hotel—in the village of Molyvos on the Greek island of Lesvos— to open for the new season. Our first guests were expected at any moment. Suddenly a little plastic dinghy with a family of 12 adults and four children washed up onto the beach directly in front of the hotel. They were freezing, soaking wet and scared. One of the men was paralyzed from the waist down.

My family and I were shocked, caught off guard by the unexpected arrivals. We quickly brought them towels, blankets, food and water. Since the weather was very chilly, we opened two rooms in the hotel to give them shelter.

When things calmed down, I had a moment to survey the scene before us. The smallest child, not even a year old, was playing with his siblings in our front yard. They were all wearing clothing I brought from home, a realization that brought knots to my stomach. These could have been my own children running around and this could have been my own family in such dire circumstances.

We eventually drove the family into the village so that they could continue on their way, searching for safety in Europe. Little did we realize that this was only the beginning of a tsunami of human suffering we would witness for months to come.

Slowly and steadily, one boat turned to two boats, then three, four, until we reached eight boats arriving each day, packed with 40 to 50 refugees.

For my family and others on the island, daily routines changed dramatically. We had to get organized. The arrival of a boat meant that we stopped whatever we were doing and ran down to the beach to offer first aid, food, drink, clothes and, finally, transportation up to the village. We then would return to clean the beach of debris—boats, life jackets, rubbish and wet clothes—to prepare for the next boat to arrive. Our hotel guests who witnessed this rose to the occasion and stood by our sides to help. They would cry with us, laugh with us, and look into the eyes of the thousands of desperate people who were arriving.

In October 2015, more than 6,200 refugees surged onto the island of Lesvos in one 24-hour period.

In October 2015, more than 6,200 refugees surged onto the island of Lesvos in one 24-hour period.

If you had asked me upon graduating from UTD where I imagined I would be in 20 years’ time, I would probably have responded, “CEO of a major multinational corporation” or “owner of a chain of hotels worldwide.” My wildest dreams would never have placed me on the frontlines of one of the greatest immigration crises that our world has known since World War II.

There are no images, no words, that can express the highs and the lows felt each time a boat comes. In that moment, there is an awakening to the realization that these human beings willingly risked their lives and the lives of their children by dealing with human traffickers, paying thousands of dollars to cross the Aegean Sea in deathtrap dinghies, all because there truly was nothing more to lose. This was, in fact, their last hope.

I will never forget the day one family left behind a pair of keys on one of the hotel sunbeds. My father picked them up and yelled, “Wait, you have forgotten your keys.” The head of the family turned and replied in a heavy tone, “Keep them. We have no need for them now. They belong to a home that no longer exists.”

Keep them. We have no need for them now. They belong to a home that no longer exists.

Very few boats have arrived since early 2016, due to the EU (European Union)-Turkey Joint Action Plan to address the emergency situation along the Eastern Mediterranean-Western Balkans route. But tourism on the island of Lesvos still has been greatly affected.

I often wonder what will become of all of us. We live in divided communities. The refugee crisis has brought out the best and the worst in humanity. It is a crisis not only for the refugees themselves but also for the local communities.

At the Aphrodite Hotel, we faced a nearly 85 percent decrease in bookings. Almost all our personnel had to be let go and we are now dealing with the challenge of making sure we do not lose our business entirely. The EU and the Greek government can protect businesses under these extreme conditions, by freezing our taxes and loans, just like they would if there had been an earthquake or hurricane. Otherwise, ours and many others’ businesses are in danger of ceasing to exist if this crisis continues.

Unfortunately, the press is not portraying the reality of what life is like right now on the island as it returns to its normal pace. At the same time, we are now ready to face any future challenges brought by the refugee crisis.

I have come a very long way since UTD. After graduating with a bachelor’s degree, I continued on my personal “fast track” with an MBA from Thunderbird School of Global Management, an American graduate school, that included two semesters spent at the Archamps campus in France.

I came to realize that success meant nothing if it wasn’t hand in-hand with a quality of life and personal happiness. By 2004, I was finally ready to enter the family hotel business, to start a new life in the picturesque village of Molyvos, Lesvos, and to lay

down roots by marrying my childhood sweetheart, Panagiotis Mariolas, and creating a family together.

The Aphrodite Hotel, however, is open only six months a year, so I had to decide how I would employ myself for the remainder of the year. My mother, Melpomenie Vati, created a school in the village in 1986, where she taught English as a second language to local children. She had been whispering in my ear for years to come back and teach by her side because she believed that teaching was my true calling. I wouldn’t admit it then, but I will now—she was right. Thus, I received my teaching license, went on to renovate my mother’s school, and brought the first interactive whiteboards to the island, revolutionizing our classroom teaching methods and making life a lot more fun and interesting for both ourselves and our students.

As a mother and a teacher myself, I can’t help but wonder how the migration crisis is affecting our children as well as the refugee children uprooted from their homes, their schools and their families and forced to exist in a state of limbo. The children of today, many who have witnessed war, terrorism and death, are watching us. We hold in our hands the power to create, through our actions and our voices, a future generation of racists or a future generation of humanitarians. Only through kindness, empathy and acceptance may we have any hope of countering

the foundations of terrorism. By closing our borders, by closing our hearts to each other and looking the other way, we are only fueling fear, hatred, racism and terror in the hearts of not only the refugees but ourselves as well.

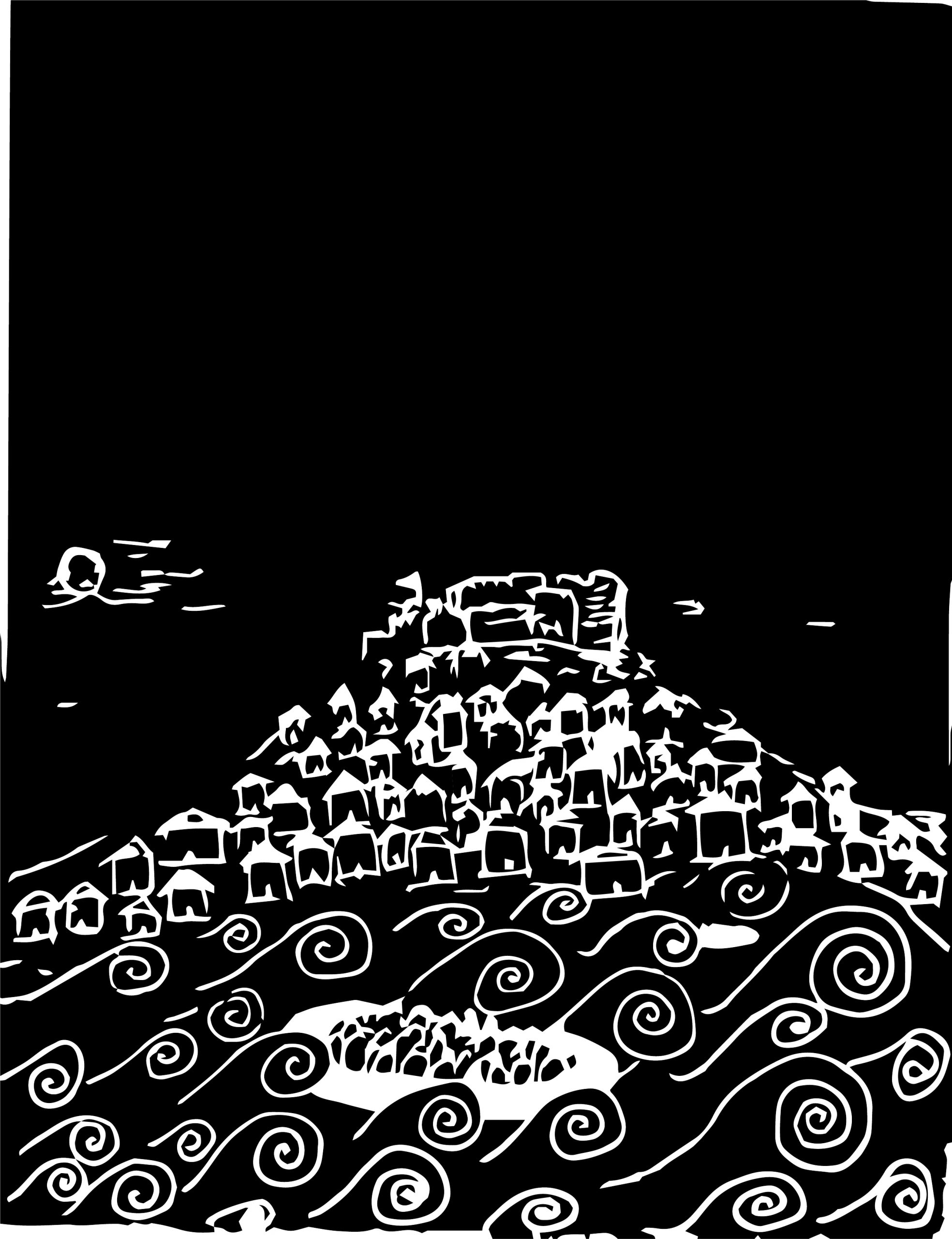

The Greek island of Lesvos has been struggling to deal with what is being called the greatest migration surge since World War II. From January 2015 to January 2016, close to 500,000 refugees arrived at Lesvos, accounting for more than half of the migration influx to Europe through Greece. Clothing and life vests left behind by the refugees were piled on the beach.

In the years since leaving UTD, and especially over the last year, I have come to understand how interconnected we truly are. Even though a problem may seem so distant from us, it is in fact much closer than we realize. We are united by a common need for freedom, peace, education, work, respect and a home. I believe that it doesn’t matter where someone is from. Neither does it matter what beliefs are held nor what professions they practice, what language they speak or what they look like. It is not “us” against “them” or “me” against “you.”

I don’t know where my path will continue from here. But I do know that I am who I am today greatly because of UTD— because of the amazing people I met there and the professors who helped us obtain and create knowledge as well as guided us to be in service of others and to strive for excellence. For that I will always be thankful.

About the Author

APHRODITE VATI MARIOLA BS’97 (standing second from left) was one of the first student ambassadors at UT Dallas. Aphrodite recalls fondly her days at the University. “When I think back to my days there as an undergraduate student, I can’t help but smile. I am grateful to possess memories of late-night studying in the Waterview Apartments, of searching for dinosaur fossils with Dr. Homer Montgomery in Big Bend, of helping create the Student Ambassador Program, of reading The Odyssey with Dr. Dennis Kratz, of acting out scenes from Shakespeare with Dr. Frederick Turner, and of Dr. Hobson Wildenthal welcoming me to campus as a freshman.”

After earning a degree in statistics, Aphrodite attended graduate school at Thunderbird School of Global Management. She completed a six-month internship in the marketing department of Delphi Automotive Systems in Wuppertal, Germany, before getting her MBA and going to work for multinational corporations in Athens, Greece. She eventually returned to Lesvos and today works with family in running the Aphrodite Hotel and the Melpomenie & Aphrodite Vati Language School.