Never Again

For 35 years the Holocaust Studies Program at UT Dallas has been a beacon of scholarship and enlightenment regarding one of the most traumatic events in human history.

By Phil Roth

From 1933 to 1945, Jewish citizens and others who lived in countries throughout Europe were rounded up and killed in Nazi concentration camps. Among the 6 million Jews who were killed in the Holocaust and the 5 million others murdered for ideological or behavioral reasons – as well as those who survived – there are millions of life stories, many of which carry on in families and communities today.

Scholars associated with The University of Texas at Dallas’ Holocaust Studies Program have been telling those stories and studying the lessons of the Holocaust for years. Over three decades, the program has evolved from a single college course into the Ackerman Center for Holocaust Studies, a groundbreaking center with an international reputation for excellence in its diverse research, educational and outreach efforts. The individuals who have contributed to the program’s and the center’s success have their own stories of how they came to participate in a cause that has brought invaluable intellectual and ethical perspectives to UT Dallas students, North Texas and the larger global community. Their dedication to initiating and promoting study of the Holocaust has resulted in insights that are as vital to understanding the past as they are to contextualizing the present and informing the future.

“We are the best example of stories that are different but that have brought people together,” said Dr. Nils Roemer, director of the Ackerman Center and interim dean of the School of Arts and Humanities (A&H) and of the School of Arts, Technology, and Emerging Communication. “The Ackerman Center must remain a place where people with all kinds of stories can find a home.”

The Beginning

Dr. Zsuzsanna Ozsváth knows the Holocaust because she lived through it. She was 9 years old in 1944 when the Nazis invaded Hungary, her native country. By May of that year, the Jewish population of Hungary had been forced into ghettos but had not been moved to concentration camps.

“I was very lucky,” Ozsváth said. “We lived in Budapest, which was the only city from which the Jews were not deported to Auschwitz. Everywhere in the countryside, virtually all the Jewish children were killed.”

Ozsváth and her family faced even more hardships under the country’s communist postwar government.

Ozsváth married young and later, during the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, she and her husband fled to Germany, eventually immigrating to Texas in 1962.

In 1963 Ozsváth’s husband, Dr. Istvan Ozsváth, a noted theoretical physicist and mathematician, joined the Graduate Research Center of the Southwest, which in 1969 became UT Dallas. Dr. Zsuzsanna Ozsváth joined the University’s faculty in 1983. Dr. Istvan Ozsváth died in 2013.

Although she initially served as a professor of literature and history in the 1980s, Ozsváth began teaching a class about the Holocaust.

“I started to study the entirety of the Holocaust. I was aware of every detail and began to publish and teach on the topic,” said Ozsváth, who is affectionately known as Zsuzsi. “After I started teaching, there were more and more students wanting to take the courses, so we added more and more classes.”

The fledgling Holocaust Studies Program, established in 1986, continued to grow as doctoral students participated. It gained additional support when Dr. Hobson Wildenthal, who joined UT Dallas in 1992 as provost and executive vice president, championed the program.

“It started out strictly with a part-time faculty member with a lot of charisma and a lot of dedication,” Wildenthal said in an interview shortly before his death in 2021. “I was happy to help any faculty member who had some ‘get up and go.’”

In November 2019 Wildenthal received the inaugural Edward M. Ackerman Leadership Award from the center in recognition of his pivotal role in growing the Holocaust Studies Program and fostering community support for the center. At a dinner recognizing those efforts, James B. Milliken, chancellor of the UT System, emphasized the importance of the Ackerman Center to the UT System and to the world.

“The Ackerman Center for Holocaust Studies is one of the crown jewels in the UT System. It’s one of … [the few] places in the U.S. where you can take graduate-level courses in Holocaust studies and a source of great pride for me and everyone associated with the UT System,” he said. “But it is my hope, paradoxically perhaps, that over time it will become if not less special, a little less unusual, because the world needs more Holocaust education.”

The Early Supporters

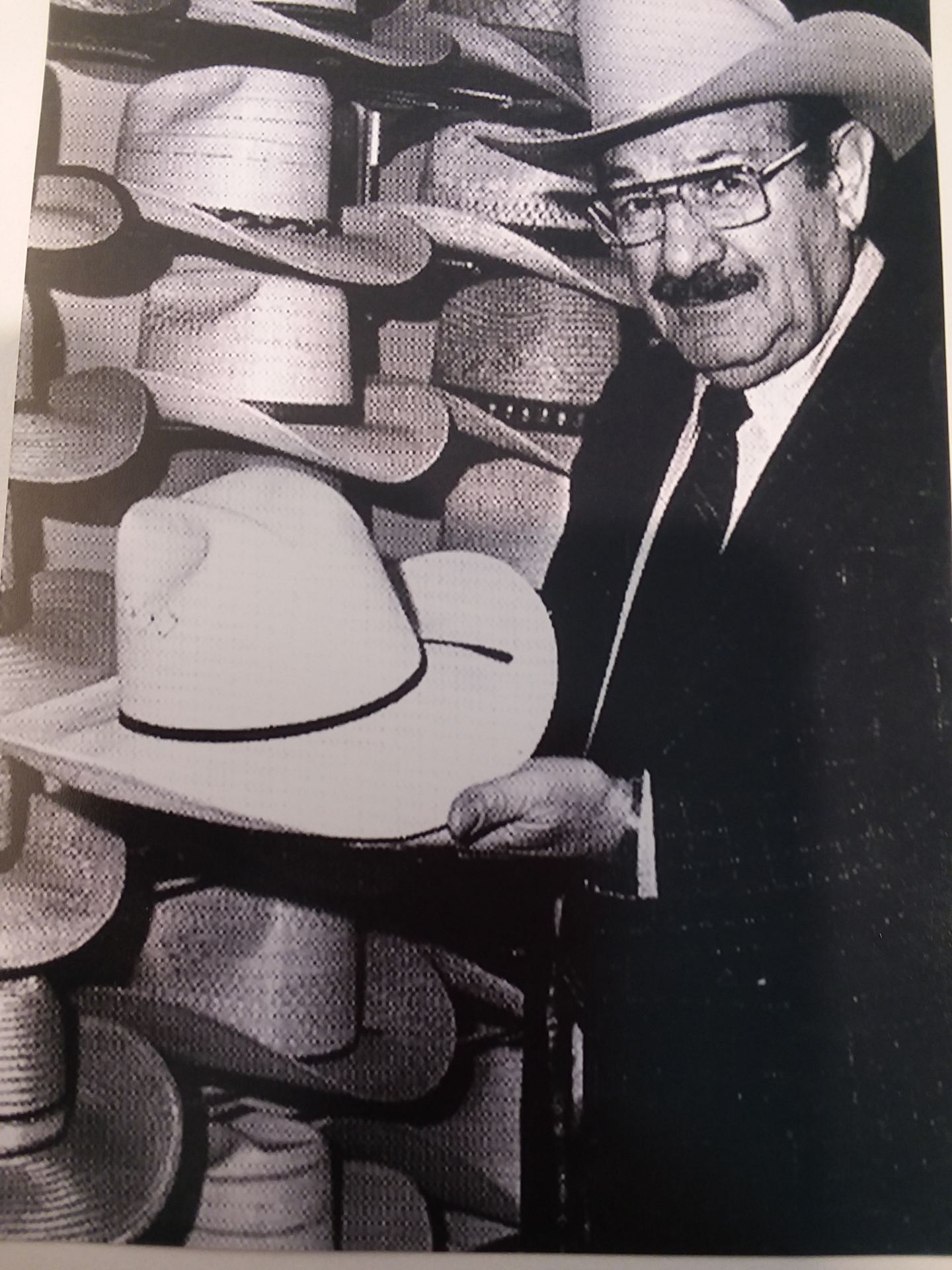

After a successful career as a Western hat maker, Arnold Jaffe wanted to go back to school and complete the college studies that had been interrupted by the Second World War and his service in the U.S. Navy. In 1980 he enrolled at UT Dallas, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in 1982 and later a master’s degree. In his studies, he took a variety of classes in A&H. One of those was called Holocaust and was taught by Ozsváth.

Jaffe was an avid reader and especially enjoyed reading 20th-century history. The class seemed a perfect fit.

“He was really interested in history, and he obviously was affected by the events of the Second World War. I think the two of them came together from both a personal and intellectual perspective,” said his son, Michael Jaffe. “It was a topic that captured his attention.”

As Arnold Jaffe took more Holocaust classes, Ozsváth said it was clear that he was a student who loved learning.

“He was enormously interested in the whole program, and he learned so much. As he attended classes and events, he was more and more delighted,” Ozsváth said.

After earning a master’s degree in interdisciplinary studies in 1984, Arnold Jaffe embarked on a doctoral studies program, which was not completed at the time of his passing in 1986. Throughout his time at UT Dallas, he often said it was important to have research materials available for those who wanted to study the Holocaust.

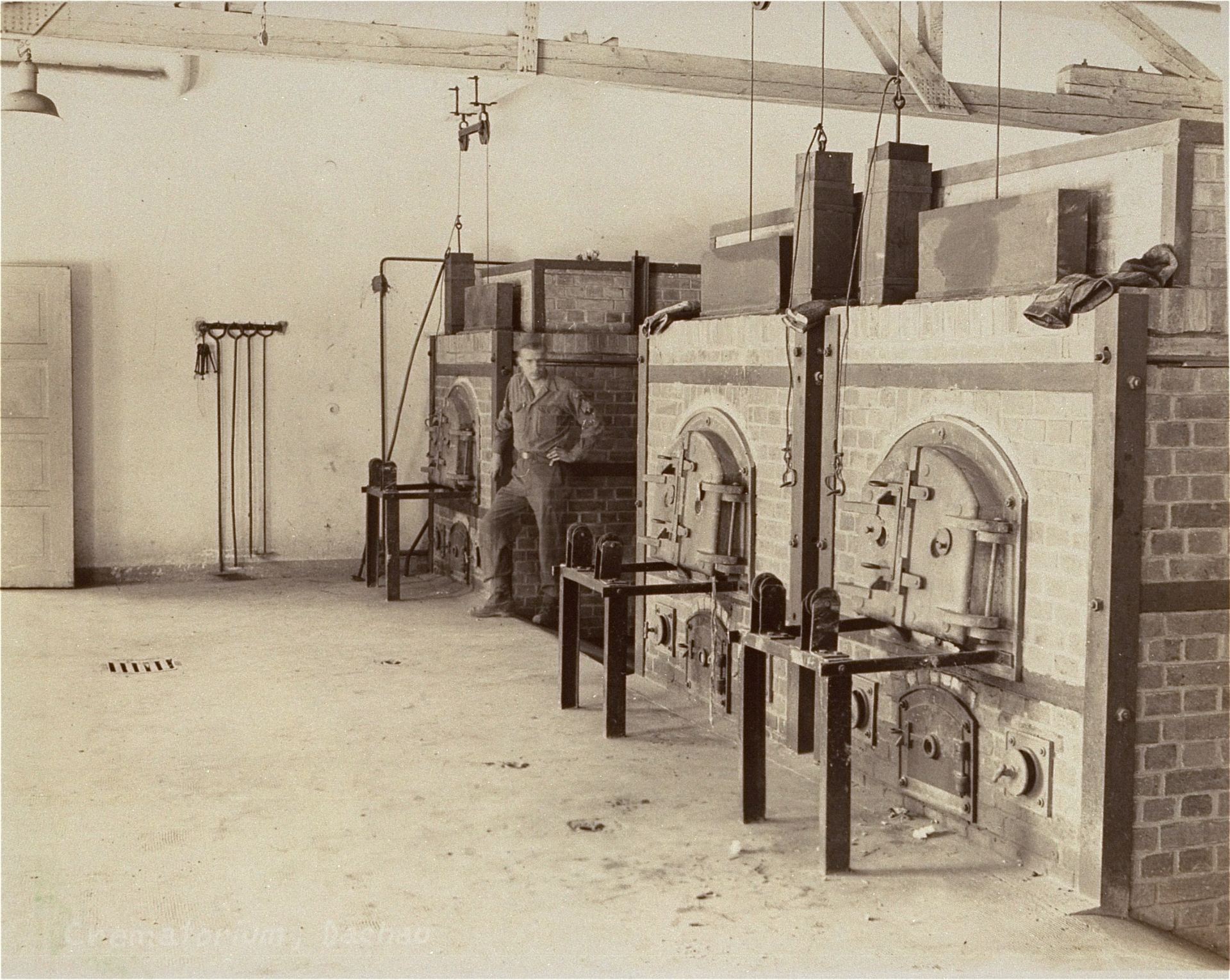

(United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Francis Robert Arzt)

After his death, his family wanted to help fulfill that dream and, with the help of friends, created the Arnold A. Jaffe Holocaust Library Collection. The endowment has provided for the acquisition of thousands of books, videos and electronic materials covering various aspects of the Holocaust.

“My father’s interest in this topic is something that was important,” his son said. “Studying and shedding light on the Holocaust and other, more recent atrocities benefits all of us.”

The Jaffe Collection gift was followed by other donations that helped the Holocaust Studies Program grow – in numbers of faculty members and classes offered, as well as in reputation.

Donors who became involved in the Holocaust Studies Program through the Jaffe Collection began looking for additional ways to support the effort. For example, a 2002 gift from Dallas psychiatrist Dr. Burton Einspruch established the Burton C. Einspruch Holocaust Lecture Series, which brings eminent scholars and international figures in the field of Holocaust studies to the UT Dallas campus.

The 1990s brought another interested supporter to the University. Edward M. Ackerman, a prominent Dallas investment advisor, philanthropist and community leader who died in 2016, made his first donation to the Holocaust Studies Program in 1993 and became even more interested in the work being done.

“When he was around the students, he would light up with energy,” said David B. Ackerman, Edward Ackerman’s son. “I just think this notion of young people learning about the Holocaust, studying the Holocaust and being able to pass that knowledge on got him very excited.”

According to his son, Ackerman gained an academic appreciation of Holocaust studies via his interest in education. Edward Ackerman’s emotional connection to the topic was derived from the family history of his wife, Wilhelmina Ackerman.

“My mother’s family suffered greatly and lost loved ones during the Holocaust in the Netherlands,” David Ackerman said.

In 2006 the elder Ackermans made the lead gift to transform the Holocaust Studies Program into a UT Dallas center bearing their name, the Ackerman Center for Holocaust Studies. Most recently, the Edward and Wilhelmina Ackerman Foundation made an additional $1.1 million gift to the center.

Dr. David Patterson, professor of literature and history, said most university-based programs that focus on the Holocaust don’t have the luxury of a dedicated facility.

“They have faculty pieced together from various departments and don’t have a central office,” he said. “Here we have our own space, five endowed faculty appointments and our own budget. None of this would exist without generous supporters in the community.”

In 2020 a major gift to the Ackerman Center from longtime supporters Mitchell L. and Miriam “Mimi” Lewis Barnett established the center’s fifth endowed chair, the Miriam Lewis Barnett Chair for studies related to the Holocaust, genocide and human rights, propelling the center to the top tier of Holocaust research programs in the country. The Barnetts have supported the program since 2002, when they created the program’s first endowed faculty position, the Leah and Paul Lewis Chair of Holocaust Studies, which Ozsváth held until her retirement. In 2018 they established the Mitchell L. and Miriam Lewis Barnett Lecture Series.

The Barnett family’s history of support for Holocaust remembrance began with Mimi Barnett’s parents, Leah and Paul Lewis, who began promoting the cause after the end of World War II. The couple sponsored a series of national memorials and were instrumental in the construction of the Lewis Park of Memories at the Dallas Jewish Community Center. Paul Lewis was appointed by former President Jimmy Carter to serve as an adviser to the first President’s Commission on the Holocaust.

The Scholars

Until her retirement in 2020 at age 87, Ozsváth was the heart and soul of the Ackerman Center, charming and delighting students, as well as community supporters. But as she ended her tenure at UT Dallas, Ozsváth was surrounded by a number of other scholars who are continuing their research and who have their own stories regarding the Holocaust and its impact.

Roemer, the Stan and Barbara Rabin Distinguished Professor in Holocaust Studies – established with a gift from the Edward and Wilhelmina Ackerman Foundation in 2007 – grew up in Germany in the 1980s, a time, he said, when memories of World War II still lingered in Europe.

“One of the things that happened when you grew up in Germany in that time period was that when you and your friends traveled to Paris or London and were joking a bit too loudly in German, people would turn their heads,” Roemer said. “Not everyone wanted to hear loud German, and you very quickly realized that being German was a little bit different than being French or English.”

According to Roemer, that environment compelled many young Germans to become more interested in the Holocaust and Jewish history. For Roemer, that interest took him to Israel for two years, where he volunteered with Action Reconciliation Service for Peace, a German peace organization founded to confront the legacy of Nazism.

“That’s where I think everything ultimately kind of came together and fermented,” he said.

For Patterson, it was a gift from a student – a book by famed Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel – that started his journey toward teaching about the Holocaust. At the time he had just earned his PhD and was teaching literature at the University of Oregon.

“I didn’t know who Elie Wiesel was, so I read it. I was so taken by it that I read everything he wrote, and then I read hundreds of other books about the Holocaust that he didn’t write. It was the reading of that memoir that started me on this path of studying the Holocaust,” Patterson said.

Patterson, the Hillel A. Feinberg Distinguished Chair in Holocaust Studies – established by Feinberg and Mr. and Mrs. John H. Massey in 2007 – said he gets uneasy when he hears teachers and students saying that they must make the Holocaust relevant.

“It’s relevant to anyone who has a soul,” he said. “When I stand in front of a classroom, I have to stand for something. I’m bearing witness to something. I’m making students into witnesses. Studying this is traumatizing. Teaching it is traumatizing. Many, many times I’ve had students in my office crying. It’s very demanding intellectually and emotionally for scholars who study it.”

The Future

Roemer said the Ackerman Center has become a “formidable” institution in the study of the Holocaust, with national and international recognition. In 2018 the center became the permanent home of the Annual Scholars’ Conference on the Holocaust and the Churches, which brings together people of various backgrounds to discuss the Holocaust from historical, philosophical and theological perspectives.

Roemer said he wants to continue the international outreach by providing more overseas internships and study opportunities for students, while also attracting students to campus from throughout the world, as well as new faculty members.

“There’s nothing in Zsuzsi’s story or mine or David Patterson’s that would have suggested that we come together,” Roemer said. “But I think that’s exactly what I want the Ackerman Center to be – a hub that attracts people from all kinds of walks of life and from all kinds of places in ways in which we can’t even anticipate.”

Last fall, new visiting assistant professor in film and Holocaust studies Dr. Emily-Rose Baker arrived on campus from England after earning bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees from the University of Sheffield. Her research examines the legacy of the Holocaust and Jewish persecution in Central and Eastern European art, literature and film after 1989.

Debbie Pfister BA’78, MA’01, PhD’09, research assistant professor in Holocaust studies, has helped to bring prospective graduate students to campus by fostering a relationship with the U.S. Air Force Academy. Her outreach has resulted in several new initiatives, including an upcoming joint conference in fall 2023, an annual summer Air Force Academy cadet internship and a visiting scholar program. Pfister began her academic journey at UT Dallas in literature as an undergraduate and now, as a faculty member, her classes have grown alongside the Holocaust Studies Program in size and popularity.

Dr. Amy Kerner is the newest tenure-track faculty member in the center. She joined UT Dallas in 2020 as an assistant professor in Holocaust and human rights studies and as a Fellow of the Jacqueline and Michael Wald Professorship in Holocaust Studies, which was established in 2017 with a gift from the Walds.

With a doctorate in history from Brown University and master’s degrees from the London School of Economics and Political Science and Columbia University, she previously was a research fellow at the Jean and Samuel Frankel Center for Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan.

“I am pleased to be in a role that brings Holocaust studies and human rights together, with a focus on Europe and Latin America,” Kerner said. “That’s unusual and an excellent fit for me. The possibility of being connected to both a history department and to a Holocaust studies center, and to bridge those fields, is very exciting.”

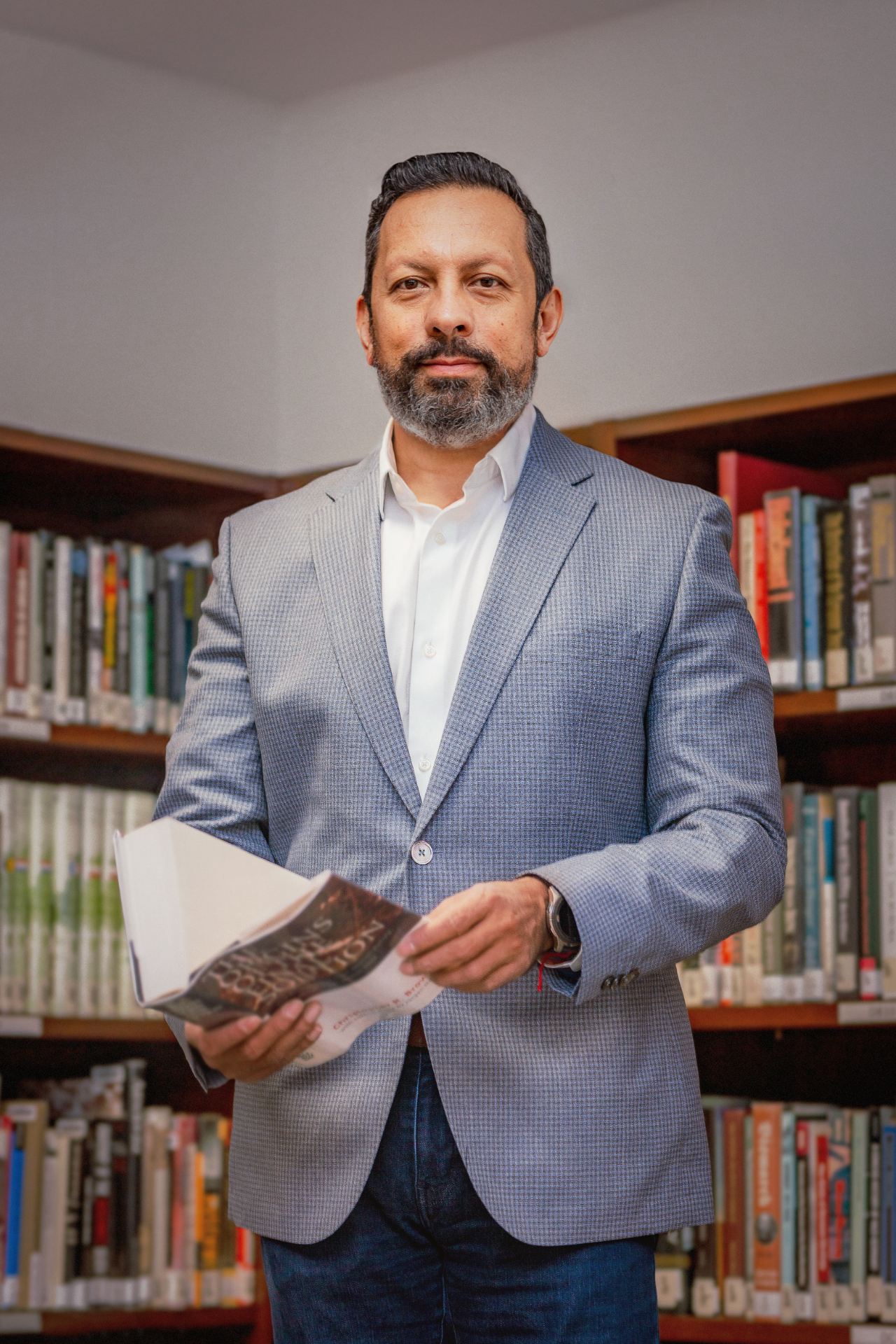

Pedro Gonzalez Corona PhD’19, assistant professor of instruction in Holocaust studies, also studies and teaches about human rights, particularly in the context of the Holocaust. He said that as he grew up in Mexico, he saw people thinking less of others and was motivated to counter that kind of attitude.

“The catastrophe of the Holocaust was perpetuated not by evil monsters or aliens, but by regular human beings,” he said. “The main lesson we should take from that is that it is far too easy to lose one’s way and end up engaging in genocidal, racist or violent behavior.”

Gonzalez Corona said the Ackerman Center fills an essential role in keeping the past alive so that the future can be brighter.

That is the kind of forward thinking that excites Ozsváth, who calls the UT Dallas Holocaust Studies Program “one of the miracles of the world.” Even in her retirement from formal teaching, her life story moves forward with translation work and other writing. She said she looks forward to seeing the center continue to grow and thrive.

“I am very optimistic,” she said. “I think it has wings right now and is ready to fly.”