Dr. Chandramallika Basak

Chess experts are known for their ability to recall configurations of chess pieces on a board. For decades, neurological experts have investigated how this memory functions and whether it can be applied to information beyond the gameboard.

To further probe this topic, researchers from UT Dallas’ Center for Vital Longevity (CVL) turned to the University’s chess team. The researchers tested 14 chess team members, along with 15 chess novices, on rapid-fire processing of visuospatial information in working memory.

“Prior studies have shown that chess experts’ advantage in visual memory is limited to chess pieces on chessboards,” said Dr. Chandramallika Basak, associate professor of psychology in the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences. “We wanted to see whether the expertise generalizes beyond chess pieces to unfamiliar, new stimuli, and where does this expertise break down for immediate memory.”

Chess masters’ visual short-term memory for arrangements that can occur in chess has been of particular interest to cognitive scientists, said Basak, director of the Lifespan Neuroscience and Cognition Laboratory.

“It’s almost like chess experts have snapshots of these positions; they demonstrate remarkable visuospatial working memory, given that the information is presented for less than half a second,” she said.

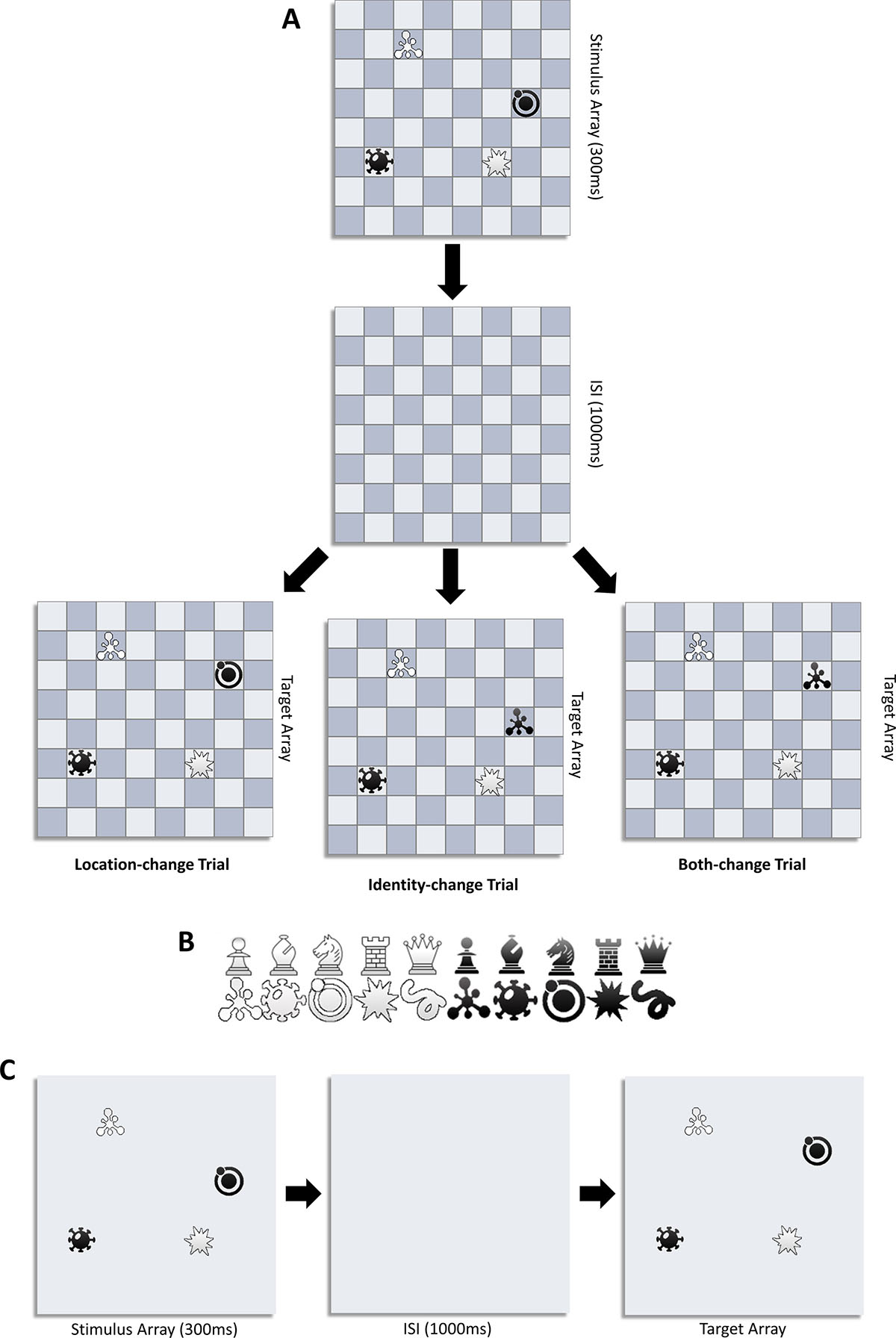

In each test, participants saw a two-dimensional chessboard with a number of pieces displayed for three-tenths of a second. After a one-second pause, they saw a second chessboard and had to decide if there had been a change. The tests were conducted with standard chess pieces and with unfamiliar symbols.

“One series of tests asks about changes in location; the second asks if the objects — the pieces themselves — have changed,” Basak said. “A third test incorporates changes in location or changes in object, or both, or no change at all. Finally, the grid of the board is removed.”

The researchers found that while both chess experts and novices performed better with chess stimuli than with the unfamiliar symbols, the experts outperformed the control group for both chess stimuli and for the new objects — particularly when detecting positional changes. When changing the identity of the objects, however, but not location, the chess players’ advantage was limited to the chess pieces.

“We observed an eight-item working-memory capacity for chess experts,” Basak said. “We assume that ties back to the idea that chess players are viewing the board and the set of positions as a single object, as they would recognize a face.”

The “grid-versus-no-grid” portion of the study — something that Basak said has not been examined before — produced some of the more striking results.

“Any expertise-related advantage disappeared in the absence of the chessboard display. It appears to be essential, acting as a road map, a familiar framework to aid the memory,” she said.

The results indicate that visuospatial memory advantages associated with chess expertise extend beyond chess stimuli in certain circumstances, but the grid appears to be necessary for experts to leverage these advantages.

The findings were published June 14, 2021, in Memory and Cognition.

— Stephen Fontenot