President and Mrs. Kennedy greeted an enthusiastic crowd near a fence at Love Field before embarking on a motorcade through downtown Dallas. The president and his entourage had arrived aboard Air Force One on the morning of Nov. 22, 1963, after a very short flight from Caswell Air Force Base in Fort Worth.

By Teri Brooks

Editors’ Note: This feature appears as it was published in the fall 2013 edition of UT Dallas Magazine. Titles or faculty members listed may have changed since that time.

John F. Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963, was a tragedy that devastated the nation. The many details surrounding the president’s death 50 years ago have been widely reported. Less well known is the connection between the Graduate Research Center of the Southwest (that would one day become UT Dallas) and the president’s visit.

Al Mitchell had an assignment: Draft plans for the possible visit of President John F. Kennedy to the Graduate Research Center of the Southwest.

In less than two weeks, the president was due to arrive in Dallas. And if the local chamber of commerce and political leaders had their way, a stop at the Graduate Research Center would be on the itinerary. These early, heady days of the nation’s space race with the U.S.S.R. had captured the imaginations of businessmen and ordinary citizens alike.

The not-quite two-year-old research center was ready to stake its claim in the region’s burgeoning science and technology sector. Mitchell, as the person responsible for the Graduate Research Center’s public relations and media coverage, welcomed the president’s visit as a showcase for the institution.

Mitchell and the center’s leadership—including Erik Jonsson and Lloyd Berkner— were faced with the realities of planning around an ever-shifting presidential itinerary. “I confess,” Mitchell wrote in a Nov. 14 memo, “to being a bit in the dark on the boundaries and limits of planning actions for the president of the United States.”

More than 2,500 guests at the Dallas Trade Mart stood, with heads bowed, after hearing the news that the president had been shot en route to the luncheon honoring him. President Kennedy was scheduled to give a speech that lauded the Graduate Research Center of the Southwest. Among the guests were many GRCSW scientists and their spouses.

When the campus visit was eventually scrapped, the center became the lead sponsor of the main event—a luncheon at the Dallas Trade Mart.

To make the most of this moment in the national spotlight, Mitchell detailed three options for consideration.

The most elaborate of the plans would require a helicopter, a military honor guard and a high school band. The proposal had Kennedy presenting to Berkner a flag that had flown over the nation’s Capitol. The flag would be couriered (probably by a center scientist) from the site of the presentation at the Dallas Trade Mart via helicopter to the Richardson campus. A closed-circuit broadcast from campus would show the courier being met by the honor guard and band, awaiting Kennedy’s command to “raise the colors” with the new flag.

Another plan drew from the World War II military service that linked Kennedy and Berkner. Kennedy famously commanded a U.S. Navy patrol boat, PT-109, in the Pacific campaign and Berkner, as a rear admiral in the U.S. Naval Reserve, gained global recognition for the scientific breakthroughs he fostered. In this scenario, Kennedy would present to Berkner a ship’s bell, engraved with a quotation from Kennedy’s 1960 inaugural address. The thousands in attendance at the luncheon, including national journalists, would then get a glimpse of the center through film clips of the October dedication of the building known today as Founders.

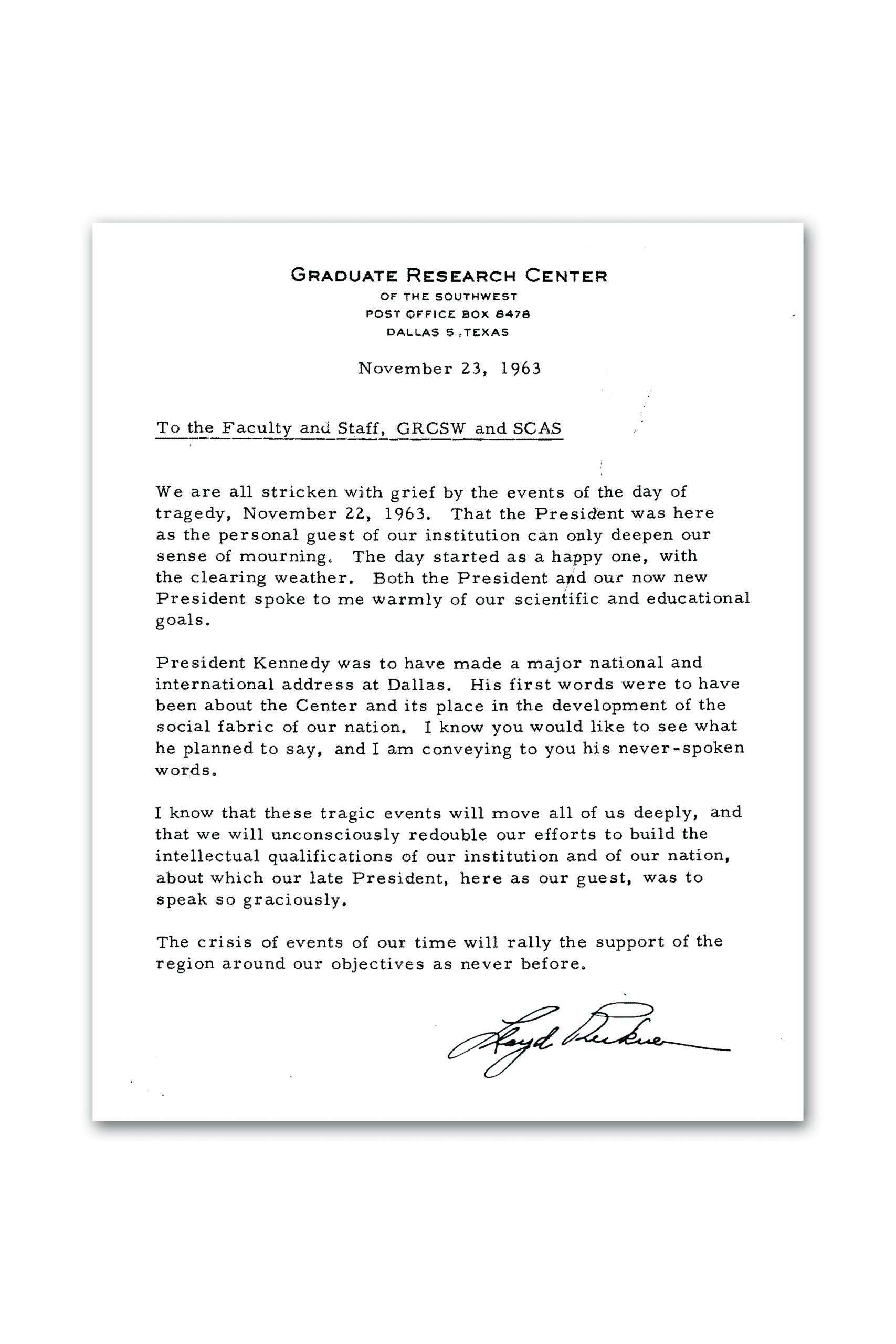

With this memo, Lloyd Berkner provided a copy of the speech that President Kennedy was to have delivered on Nov. 22, 1963.

Simplest of all, and the eventually agreed upon plan, was one in which Kennedy would talk about the Graduate Research Center at the beginning of his scheduled speech at the Dallas Trade Mart. All of the center’s scientists and their spouses received invitations to the luncheon so that they could hear the president publicly acknowledge the value of the work they were conducting.

Fate intervened, however. The carefully crafted agenda was abandoned when word came that Kennedy and Texas Gov. John Connally had been shot while riding together in an open car through downtown Dallas on their way to the Trade Mart. Mitchell later wrote: “The somewhat-nagging question remains: If President Kennedy had been taken by helicopter to the campus, and thence to the Trade Mart, would the course of history have been changed?”

Mitchell’s question can never be answered. But the president’s undelivered speech remains. Obtained from the Associated Press that same day by Mitchell, the speech was reproduced and distributed to center employees, along with a note from Berkner.

The afteraffects—the stigma—felt in Dallas following the assassination also affected the center’s scientists. Registrants began to cancel for a RCSW sponsored meeting on “Gravitational Collapse and Other Topics in Relativistic Astrophysics.” Organizers enlisted the help of Dallas Mayor Earl Cabell, who sent telegrams, cables and radio messages to the scientists with assurances that they would not be endangered by coming to Dallas.

Fifty years later, the astrophysics conference continues. UT Dallas will host the event in December. And the fledgling center that evolved into a nationally recognized research university remains forever linked to one of the most significant days in American history.

Denise Hales recalled attending the Trade Mart luncheon with her late husband, Dr. Anton Hales. They had moved from Johannesburg, South Africa, to Texas where Dr. Hales established the geoscience division at GRCSW in 1962.The [Dallas Trade Mart] auditorium was filled with thousands of people and yellow roses. Texans had this thing about having radios in their pockets. I don’t know who I was sitting by—whether it was Erik Jonsson or Eugene McDermott—but I heard very softly on this radio “The president of the United States has been shot.”

I leaned over to Anton and said, “The president of the United States has been shot.” Anton said, “Denise! Don’t start a rumor like that!” Anyway, I kept very quiet.

A few minutes later, Erik Jonsson announced, “The president of the United States has been injured.” Everyone stopped eating. No one touched the huge T-bone steaks in front of them. I think we said a prayer and there was silence. We must have sat there for 20 minutes. Then Erik Jonsson stood up again and said something along the lines of “The president has been shot very seriously and we are completing this event.”

Because we were in the front of the hall, we were among the last to leave. As we went out of the building, we heard on a police radio that the president had died at Parkland.

Dr. Wolfgang Rindler, a UT Dallas professor of physics in the cosmology group, joined the Graduate Research Center of the Southwest in September 1963. He was in attendance at the luncheon in the Trade Mart.President Kennedy’s visit to Dallas was to include a luncheon speech [at the Trade Mart] about the future of science. Among other things, he was going to spend quite a lot of time talking about the center.

The entire faculty of the center and their wives were invited to the luncheon in a huge building downtown. There were hundreds of tables, and President Kennedy was supposed to address that huge audience of notables from Dallas at 12:30. People were there at 12 o’clock; then it became 12:30. Somebody came to the podium and said that people should start eating, that there would be a delay in Kennedy’s appearance.

In those days people didn’t have cellphones, so once you were sitting at lunch you had no connection with the outside. But waiters coming from the kitchen had heard the radio. A waiter came to our table, and said, “Kennedy! Bang, bang, bang! Kennedy! Bang, bang, bang!” That was the first indication we had that something terrible had happened.

Then somebody came to the podium and told us what had happened. That was a terrible shock. People started crying. I think people all over the country probably cried.

For us [scientists], it was a terrible shock because Kennedy had radiated enthusiasm for science. We realized already at that point that the loss of Kennedy would really be, in the end, bad for science. But, at the moment, the human tragedy of it all just seemed overwhelming.

Many of us who came to work at the center lived through the shock. It was, in a way, a sad introduction that happened about six to eight weeks after most of us had arrived in Dallas.